The Climate Policy Database collects greenhouse gas mitigation policies

Policies included in this database are often a combination of policies with an explicit climate change mitigation objective, such as greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategies; energy policies, that help to decarbonise the energy supply and/or reduce energy demand; and policies that aim to introduce low-emissions practices and technologies to non-energy sectors, such as agriculture and land use.

In this database a policy can be a law, strategic document, a target, or any other policy document that result in lasting reduction on the country’s emissions intensity. The Climate Policy Database does not track policies covering very specific areas, such as efficiency standards for individual engine types.

The Climate Policy Database closely tracks national climate policy developments in 42 countries including the European Union (EU) (see list below) and includes non-exhaustive information on other countries. The EU is treated as a country. Coverage of subnational and supranational policies is non-exhaustive for all countries.

For more details about our methodology and the list of indicators in the database, please download our documentation.

Table: Countries frequently updated in the CPDB

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The CPDB is annually updated to include latest policy developments. These updated include new policies adopted and updates on existing policies, such as changes to the content and implementation status of policies (for example, when a policy is ended, superseded, or goes from being planned to in force).

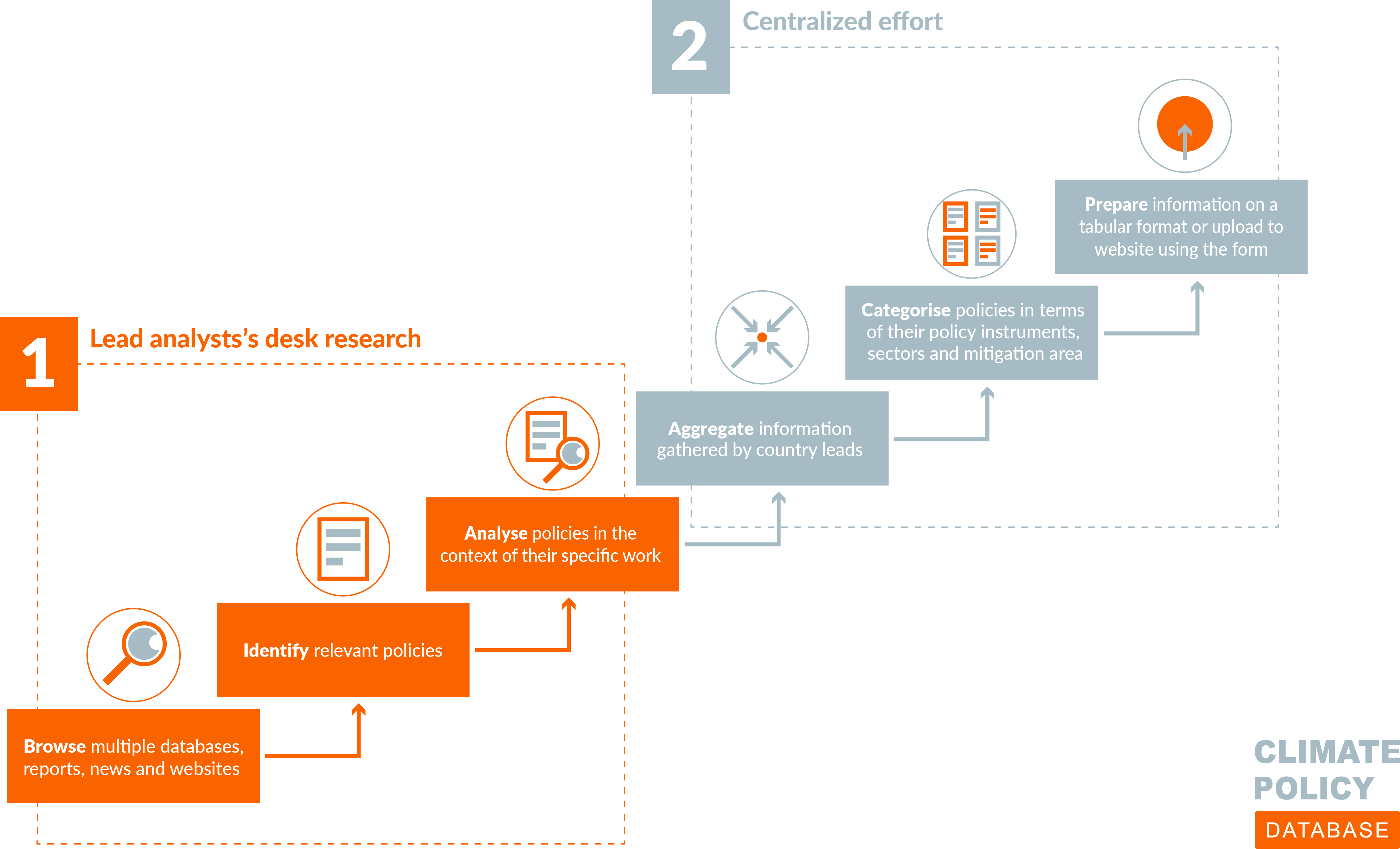

Updating the CPDB is a collaborative effort of country experts who track new policies adopted in individual countries as part of their specific work. This research process includes surveying existing policy databases (see list below), as well as analysing official government documents, third-party reports, news sites and others.

Figure: Overview of CDPB data collection process.

The CPDB core team collects information from country experts and categorises it according to the CPDB’s taxonomies (see below). New or updated policies are checked against existing policies to ensure consistency and avoid duplication. Finally new policies are uploaded to the CPDB website. A bulk update is planned every year, where the previous year’s policies are added to the database, with smaller updates also happening throughout the year.

The CPDB classifies policies in key areas according to custom taxonomies to enable comparative policy analyses. These taxonomies were developed based on extensive research on climate policies and aim at providing a menu of options in important areas, to help track progress and identify gaps in policy adoption (Nascimento et al., 2022). The CPDB classifies policies according to the following main taxonomies.

Table: Summary of key CPDB taxonomies

| Taxonomies | Elements |

| Sectors | Agriculture and Forestry, Buildings, Electricity and heat, General, Industry, Transport |

| Policy instrument types | Economic instruments, Regulatory instruments, Codes and standards, Voluntary approaches |

| Mitigation area | Energy service demand reduction and resource efficiency, Energy efficiency, Renewables, Other low-carbon technologies and fuel switch, Non-energy, Cross-area policy options |

Current and previous versions of the Climate Policy Database can also be found here on Zenodo.

The Climate Policy Database should be cited as:

NewClimate Institute, Wageningen University and Research & PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. (2016). Climate Policy Database. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7774109

The 2023 version of the Climate Policy Database should be cited as:

NewClimate Institute, Wageningen University and Research & PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. (2023). Climate Policy Database. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10869734

For more information about the taxonomies is included in our documentation or in the publication:

Nascimento, L. et al. (2022) ‘Twenty years of climate policy: G20 coverage and gaps’, Climate Policy, 22(2), pp. 158–174. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1993776.